Let α ∈ R be nonnegative and n ∈ N. Then there exists a unique non-negative x ∈ R such that x n = α.

Existence of n-th roots of positive real numbers

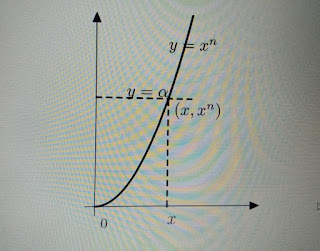

Strategy: Look at Figure 1.9. What we are looking for is the intersection of the graphs of the functions y = α and y = x n . The common point will have coordinates (x, xn ) and (x, α). Hence it will follow that x n = α.

Now how do we plan to get such an x? We work backward. Let b ≥ 0 be such that b n = α. Now b = lub [0, b) and any t ∈ [0, b) satisfies t n < α. Hence b may be thought of as the LUB of the set S := {t ≥ 0 : t n < α}. Now if S is non-empty and bounded above, let c := lub S. We hope to show that c n = α.

We show that c

n < α or c

n > α cannot happen. See Figure 1.10. If c

n < α,

the picture shows that we can find c1 > c, c1 very near to c, such that

we still have c

n

1 < α, c1 ∈ S. This shows that c1 ∈ S. Hence c1 ≤ c, a

contradiction.

If c

n > α, we can find a c2 < c, c2 very near to c

but we still have c

n

2 > α. Since c2 < c, there exists t ∈ S such that t > c2

and hence t

n > cn > α, a contradiction. Hence c

n = α.

Now c1 > c and is very near to c and still retains c

n

1 < α. How do we look

for such c1? Naturally if k ∈ N is very large, we expect c1 = c +

1

k

is very

near to c and (c +

1

n

)

n < α.

Similarly, for c2 we look for a k ∈ N such that (c −

1

k

)

n > α.

In the first case, it behooves us to use the binomial expansion. We try to

find an estimate of the form (c + 1/k)

n ≤ c

n +

C

k

for some constant C. So,

it suffices to make sure C/k < α − c

n

, possible by Archimedean property.

In the second case, we try to find an estimate of the form (c−1/k)

n ≥ c

n−

C

k

.

So, it suffices to make sure c

n −

C

k > α.

We claim that x

n = α.

Exactly one of the following is true: (i) x

n < α, (ii) x

n > α, or (iii) x

n = α.

We shall show that the first two possibilities do not arise.

Case (i): Assume that x

n < α. For any k ∈ N, we have

(x + 1/k)

n = x

n +

Xn

j=1

n

j

x

n−j

(1/kj

)

≤ x

n +

Xn

j=1

n

j

x

n−j

(1/k)

= x

n + C/k, where C := Xn

j=1

n

j

x

n−j

.

If we choose k such that x

n + C/k < α, that is, for k > C/(α − x

n), it follows

that (x + 1/k)

n < α.

Case (ii): Assume that x

n > α. We have (−1)j

(1/kj

) > −1/k for k ∈ N,

j ≥ 1. We use this below.

(x − 1/k)

n = x

n +

Xn

j=1

n

j

(−1)jx

n−j

(1/kj

)

≥ x

n −

Xn

j=1

n

j

x

n−j

(1/k)

= x

n − C/k, where C := Xn

j=1

n

j

x

n−j

.

If we choose k such that x

n − C/k > α, that is, if we take k > C/(x

n − α), it

follows that (x − 1/k)

n > α.

We now show that if x and y are non-negative real numbers such that x

n =

y

n = α, then x = y. Look at the following algebraic identity:

(x

n − y

n

) ≡ (x − y) · [x

n−1 + x

n−2

y + · · · + xyn−2 + y

n−1

].

If x and y are nonnegative with x

n = y

n and if x 6= y, say, x > y, then the

left-hand side is zero while both the factors in brackets on the right are strictly

positive, a contradiction.

This completes the proof of the theorem

Comments

Post a Comment